Parties are Supposed to be Fun

So why can't I enjoy them?

I walk into the crowded living room. My palms are already clammy, and thinking about the possibility that someone might go in for a hug or handshake makes them sweat harder. I greet the hosts and the people I know. I’m a little too intimidated to introduce myself to people I don’t know, but maybe I’ll get there later in the evening. I laugh and smile and nod because I’m having fun. Right? Parties are fun.

It’s just… I can’t… my mind is blanking… and words come out of my mouth, but I don’t think they’re quite right somehow? They must be wrong, or at least dreadfully boring, judging by the way that person turned away and started talking to someone else. Why can’t I think of anything interesting to say? I try to grab on to a lively anecdote, search desperately for a conversation starter, but there’s just… nothing there.

It’s frustrating. But I love my friends, so of course I’m showing up for their party. Parties are fun. It’s me who isn’t fun. I’m doing this wrong, I know it. But I keep that smile on. And it’s not all bad—sometimes I’ll get into a good one-on-one conversation and feel like I actually made a connection, and that gives me a little boost. That makes this whole thing feel worth it.

The worst part comes later, when I’m back at home trying to get to sleep. The whole event replays in painful detail inside my head. I mentally relive each conversation, evaluate its level of awkwardness, come up with better responses. The looping replays and should-have-saids won’t stop. Why am I making such a big deal of this? Maybe I didn’t perform as badly as I think I did… but if that’s true, why do I feel so bad? Why can’t I just enjoy myself, like everyone else does? Parties are fun. At least, they’re supposed to be. Parties aren’t the problem. I am the problem.

I am the problem.

This subconscious refrain was like a jagged pebble inside my shoe, an ever-present irritation. If this mind-going-blank issue only happened at parties, it might not have bothered me so much. But the same thing happened whenever I was put on the spot in any way—especially at school. My classmates would answer eloquent (or at least coherent) replies to the teacher’s questions, but when I was called on, I would go full deer-in-the-headlights and babble whatever came to mind. And then I would spend the rest of the day berating myself for what I had said, or what I hadn’t said, for how stupid I must have sounded.

After these experiences were repeated countless times over three decades, this is what I came to believe about myself: There’s something inherently wrong with me. I am not an interesting person. I don’t have anything to offer to the conversation.

And, worst of all: I am not as smart as they all think I am.

Growing up, I was always the Smart and Shy One™. It felt okay, though of course not ideal, to be a shy person as long as I was also smart. But if I couldn’t articulate a good answer when called on—if I couldn’t even find my thoughts at all—this was proof that I wasn’t actually smart. People thought I was, because I was good at doing assignments and taking tests, but they were wrong. One day, they would discover the truth. And then it would be all over for me.

I was convinced that blanking out in social situations was a personal failing. It wasn’t until recently that I was able to understand it for what it really was: my body’s response to perceived danger.

As a biology student, I had learned in great detail about the fight-or-flight stress response. This was usually talked about in the context of physical danger, but it occurs for psychological danger too. Any threat to safety can cause the nervous system to invoke the stress response—and “fight or flight” aren’t the only two options. The “freeze” response is also extremely common.

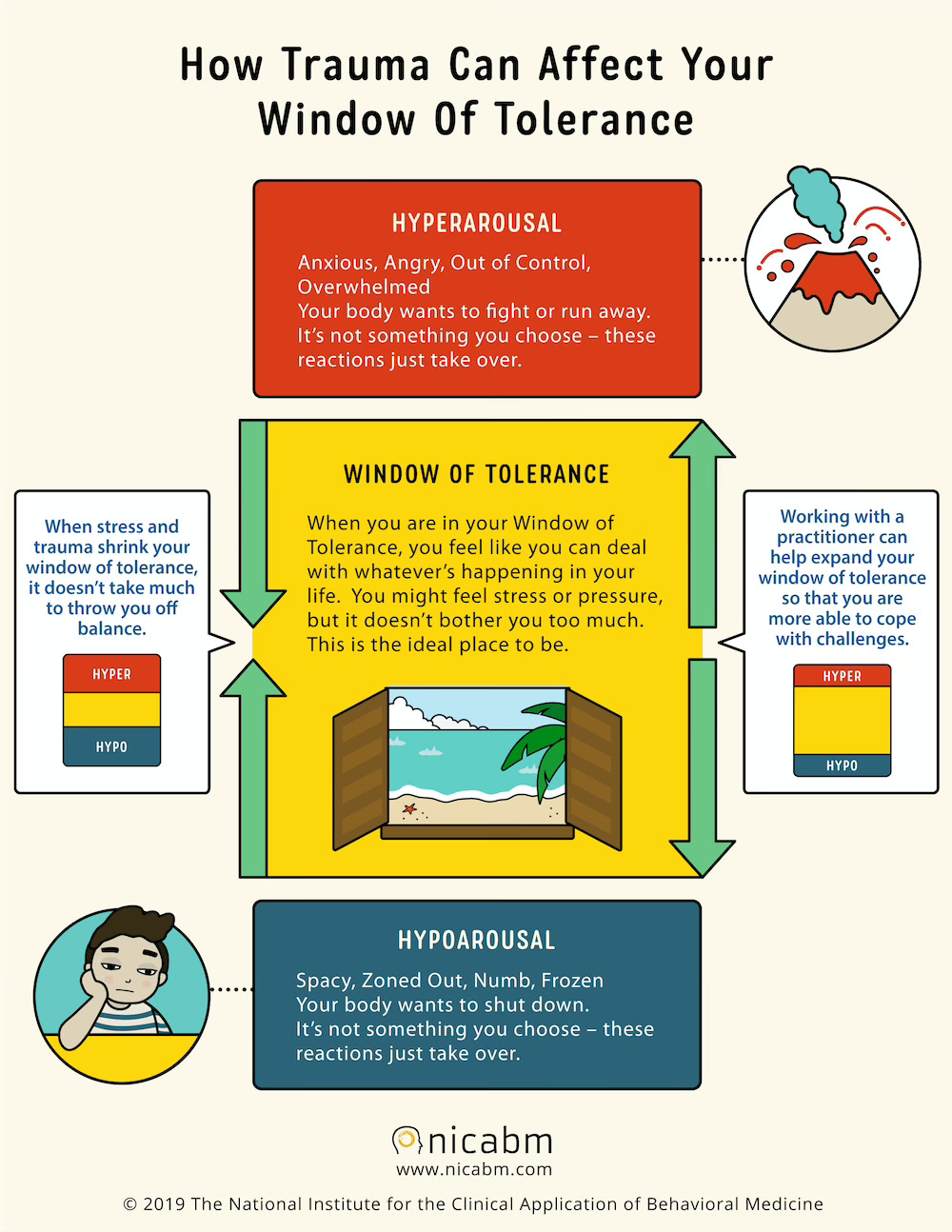

Sometimes, it doesn’t take much to provoke a seemingly-extreme stress response. I have found the Window of Tolerance to be a particularly helpful way of thinking about this.

According to this framework, which is based on polyvagal theory, we all have a window of tolerance where we feel calm, connected, and able to handle whatever life throws at us. But stress and trauma can narrow this zone, meaning that we are easily activated into either a state of hyperarousal (anxiety/fight or flight) or hypoarousal (depression/shutdown).

One day I was reading through a list of symptoms of the freeze response, and two in particular jumped out at me: mind goes blank and inability to speak. Those two little phrases filled me with so much relief that I almost kissed my laptop screen.

It wasn’t that I was fundamentally flawed. It was just that, for me, social situations were distressing. But because that distress did not look the way I expected, I couldn’t see how big of an issue this was for me. If I had been having panic attacks instead, I might have been more likely to understand my social anxiety for what it was. (Though, honestly, I may not have acknowledged it anyway, because I didn’t feel like I should be so stressed out about something that everyone else seemed to do without any trouble.)

Once I started thinking about this mind-blankness reaction as a stress response, though, it lessened some of the blame I had heaped upon myself. I began to understand it as something that is hard-wired within everyone. While we all may react differently to different stressors, we all have this inbuilt pathway. It is not an individual personality flaw. It is an essential part of how we all interact with the world.

Of course, it’s one thing to have a framework for understanding an issue… and another thing to actually work with it.

At the root of my social anxiety—and various other issues—was shame. And shame is one of the most painful emotions that we encounter. Many of us would prefer to go our entire lives avoiding it instead of facing it head-on. Myself included! I shut down in social situations because they brushed up against a raw, ashamed part of me that was terrified of rejection (which, irrational as it may be, felt like a fate worse than death). And whenever I said something awkward or felt that someone else was embarrassed on my behalf, the shame grew and grew, reaching a crescendo once I was back in my own safe bed, where every “wrong” thing I did was put on repeat inside my brain.

I couldn’t really deal with any of that until I had widened my window of tolerance enough to be able to sit with the discomfort of shame. To learn how to let my body relax into it, instead of tensing up and trying to shut it down immediately. Shame thrives on secrecy, they say, and so I started talking about it, writing about it, letting it move through instead of getting stuck in my body. I began building relationships with parts of myself that protected or held shame that had been festering for a long, long time.

It took years of slow training to get to this point. Therapy definitely helped, but I also found it useful to build distress tolerance within my physical body as well. Not by pushing it to its absolute limits, but by gently stretching. Searching for the edges and seeing if I could relax and breathe into them.

To take one example, I end every shower by turning off the hot water for a 1- to 2-minute cold blast. I would not say that I look forward to the actual experience. It always feels unpleasant at first. But after about 20 seconds under the cool waterfall, I can settle into it. Yeah, I’m not exactly cozy. But I am completely, 100% awake and in the present moment. I am alive. And to be alive is to feel the exhilaration and the dread, the joy and the pain. To know that we have so much capacity to stretch and adapt, to fall and to rise again.

And I think that’s what it comes down to: discomfort is necessary for growth. I wasn’t able to really reckon with certain issues I knew were important to face—such as, say, the internalized ableism that made me believe I was only worthwhile if I fit into the narrow standards of what our society defines as “smart”—until I had built up enough tolerance to face the shame that underlies them all.

Though the standard narrative might wrap up with a cheery Now I’m all better, and I love parties!, that’s not really true for me (yet?). I do enjoy small gatherings and good conversations, but I still struggle to speak up in certain environments and situations. I’m still learning how to stay grounded enough to find my thoughts and my voice when I’m put on the spot. I’ve been stuck in these deep grooves of habit for my whole life. Carving out new pathways takes time.

But it feels okay to muddle along and feel my way messily through it. Because in the end, I know I am not the problem. I’m alive, I’m here, I’m doing the best I can. And that is good enough for me.

I am a TOTAL NERD for polyvagal theory! Yes window of tolerance 👏🏼 I see so much self love and wisdom here 💞

This is eye-opening. I’d never heard of the window of tolerance, but now I know what happens to me when I ask a question in certain professional settings. Depending on the meeting attendees, I sometimes experience a hypo response where I can’t hear the response to my own question because I’m worried how others perceive my question. Thanks for your vulnerability and insights!